As Helene devastated western North Carolina, the state’s on again, off again landslide mapping program left many without critical safety information.

AVERY COUNTY, N.C. — Leading up to the deadliest disaster in state history, North Carolina failed to deliver potentially life-saving information about landslide dangers to people in most western North Carolina counties.

Years before Hurricane Helene, state lawmakers funded a program aimed at identifying areas vulnerable to landslides. Scientists made limited progress before politics cost western North Carolinians precious research.

An estimated 31 people, at a minimum, died from landslides, triggered by relentless rain falling on already saturated ground during the unprecedented 2024 storm.

“The worst pain you could imagine”

Melissa Guinn, a mother of four, thought she found the perfect home for her family in 2018. It sat high above the river and overlooked Highway 19E in Avery County.

Even during Helene, her husband Jamie said they felt safe. After all, the couple had no reason to think otherwise.

“We were looking at the river all morning,” he said. “Never thought nothing about behind the house. Never occurred to me.”

A year-and-a-half later, Jamie can’t bring himself to return to the site of their former home. He’s emotionally unable to step foot back on the property.

Multiple landslides destroyed the home, sent him and their son River 60 feet down the mountain into the river below and worst of all, killed his wife of nearly a decade as he stood helpless below.

“The house went into pieces. I just remembered being crushed and being in complete blackness. I had a split second of time to think, ‘This is how I die,’ and I can remember all of a sudden stopping and I could hear (River) and luckily, when we landed, we landed really close to each other and I was able to pick pieces of the roof up off a top of him,” Guinn said. “When I looked up and saw (Melissa), it was such a relief that I knew she was ok. I’m assuming another one was coming, because the last thing I heard her scream was, ‘Babe, watch out’ and I grabbed River and got him up on the bank, but by the time I looked back, she was gone. My second of relief turned into dread. I guess the worst pain you could imagine in a split second.”

In the end, something the Minneapolis family didn’t even know posed a risk destroyed the life they built.

“We never thought nothing about the mountain coming down on us,” Jamie said. “Without knowing this, it literally upended my life and changed it forever.”

State scientists wanted to prevent this

State geohazards geologist David Korte leads North Carolina’s landslide mapping program. He and his small team are now playing catch-up after the taxpayer-funded program sat dormant for nearly a decade.

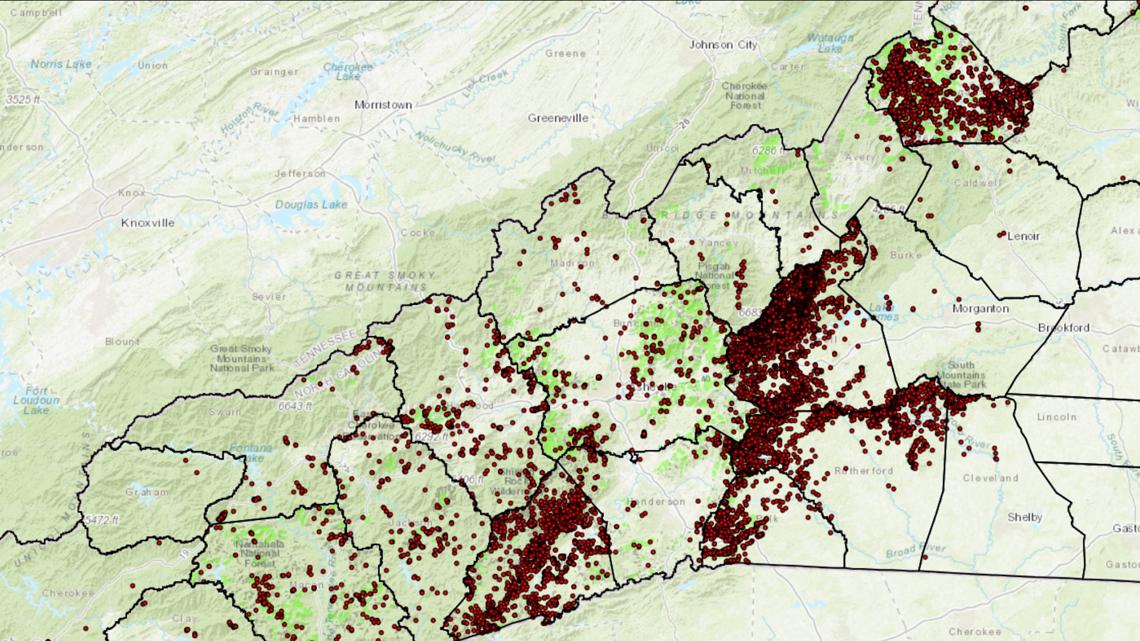

Lawmakers eventually resurrected the program. As a result, North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality geologists have spent the last seven years documenting as many historic sites as possible, knowing landslides will occur again nearby at some point.

“They tend to happen near where they’ve happened before, because of similar microclimate conditions and similar geology,” Korte said.

Their goal is to inventory every landslide in western North Carolina history. The job is an even greater challenge now, post-Helene, but also more critical than ever.

“It’s beautiful here. People want to live here, and there are a lot of places to buil,d and there are a lot of places that you can build if you are careful, and there are probably a few that you don’t want to build there,” Korte said. “This works, it’s simple and it’s not meant to scare anybody. It’s just meant to improve our decisions.”

The state geologists started posting their finished maps online for the public to see in 2021. Korte said they can serve as a warning system that indicates possible future danger. The information can help homeowners, builders and planners understand the risks and assess their comfort level.

“If you put a school on an ancient landslide deposit, you may be asking for trouble,” he said. “Could be 100 years, could be 10,000 years, could be 100,000 years, could be 10 years.”

“Some of the loss of life could have been lessened”

State lawmakers first embraced the concept of landslide mapping two decades ago, after landslides during Hurricanes Frances and Ivan killed five people.

In 2005, the North Carolina General Assembly dedicated about half a million dollars a year to create and sustain the landslide mapping program. Legislators tasked the team, then led by geologist Rick Wooten, with mapping landslides in 19 western North Carolina counties: Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Buncombe, Burke, Caldwell, Haywood, Henderson, Jackson, Macon, Madison, McDowell, Mitchell, Polk, Rutherford, Swain, Transylvania, Watauga and Yancey.

The geologists fully mapped four of those counties (Macon, Watauga, Buncombe and Henderson) and partially completed a fifth (Jackson) before the political winds shifted in 2011. Amid concerns from realtors and builders, worried about property values, liability and government regulation, the newly Republican-led North Carolina General Assembly shut down the program.

Wooten, who called the program strictly “a planning tool,” said the North Carolina Home Builders Association expressed concerns. He told WCNC Charlotte that a lawmaker at the time argued landslide mapping was essentially a backdoor approach to more regulation.

“That was the argument that won the day,” Wooten said. “My opinion is it was money well spent to keep that program running. The losses from Helene are devastating and in an ideal world where people would have had the information they needed, some of the loss of life could have been lessened and so that’s always front of mind.”

Former Rep. Ray Rapp, a Democrat from Mars Hill, who pushed for the creation of the landslide mapping program, said, as he recalls, NCHBA “managed to sidetrack” the ongoing effort.

“Today their representatives deny it, but as someone in the thick of it during my 10 years in the House, their influence carried the day,” he told WCNC Charlotte.

The NCHBA, through a spokesperson, told WCNC Charlotte the organization’s past questions about landslide mapping doesn’t equate to formal opposition to public safety improvements. Today, the organization said it supports the program.

“NCHBA supports efforts to identify and communicate landslide risks so that communities, property owners and builders can make informed decisions,” NCHBA chief of staff and director of regulatory affairs Chris Millis said. “Our members live and work in the same mountain communities affected by recent storms, and we share the goal of keeping our fellow neighbors out of harm’s way.”

Landslide mapping reborn

In 2018, as the program sat unfunded, another storm hit, prompting more deadly landslides in western North Carolina. The General Assembly, again controlled by Republicans, lifted the freeze and dedicated limited funding to the effort, which officially restarted in 2019.

Former Henderson County Rep. Chuck McGrady, who was a freshman legislator when the General Assembly first paused landslide mapping, believes his efforts many years later as budget chair helped restore the program.

“I was in a position to push it and I pushed it,” the Republican told WCNC Charlotte. “It’s one of the things I am pretty proud of.”

He said a tight budget ultimately doomed the program in 2011 and said his lack of status back then only hurt the cause.

“From the time it got cut, it’s something I thought we may have needed to do and that was a decision higher than me,” he said. “I made the pitch to not make that cut. There were a lot of things cut that year.”

In the years since the program’s rebirth in 2019, Korte said his team has mapped another five counties (Polk, Rutherford, Cleveland, McDowell and Transylvania).

“I believe this program has saved lives,” he told WCNC Charlotte.

He cited the case of a school district that reconsidered building in one location after seeing the maps, which also identify landslide susceptibility under certain conditions and debris flow pathways.

“Told them you don’t want to build the school here. You want to move it over 500 feet,” Korte said. “That’s exactly what they did.”

Moving forward

Korte’s now asking lawmakers to expand the program and dedicate recurring money so he can hire more people and keep up with the daunting workload. He told WCNC Charlotte he’s seeking an additional $2 million and six people, with more than half of that money recurring.

Among other things, he’s pushing to accelerate the state’s mapping efforts and increase public outreach and education. Instead of waiting to finish an entire county before publishing the maps online, Korte said geologists are making individual site data available as soon as it’s completed.

He said crews recently received new Helene landslide data, identified using laser technology, that will help as well.

In addition, he’s pushing for annual training at the beginning of hurricane season to better publicize the landslide maps.

“We are creating an early warning system for western North Carolina,” Korte said. “This is going to help prevent loss of life.”

As he looks forward, at the same time, it’s hard not to look back and wonder how many other counties geologists could have mapped had lawmakers not stopped funding the program for eight years. At a pace of one per year, that’s roughly eight counties that could have had finished landslide maps publicly available before Helene.

“What was the impact of this program being shut down for all this time?” WCNC Charlotte asked Korte.

“It probably decreased awareness of the landslide hazards in western North Carolina and when that could possibly happen,” he said.

What if?

By the time Helene hit, most counties in western North Carolina were unmapped, including Avery.

“Unfortunately, I think of what ifs constantly,” Jamie Guinn said. “I’d give anything if that would have already been done. I mean, that would have changed my entire life.”

With no warnings about their property, Jamie lost the most important woman in his life.

“To me, she was perfect,” Jamie said. “Guess that was the only one I ever chased. It’s kind of hard to face the fact that I don’t have her.”

He also lost peace of mind. Jamie and River remain traumatized. Now living in a different home in the shadow of another mountain, they, like people in most western North Carolina counties, still don’t know if their house is near a historic landslide site.

“It’s always in our mind,” he said. “If it gets too windy or anything, I guess I try to bury it deep down and just tell him, ‘It’s going to be OK,’ when honestly, I don’t know, but I don’t want him to feel scared either. After something like that, you’re always paranoid that the mountain’s going to cave down on you.”

He’s now speaking up in hopes of protecting others.

“I’d love to see the topic be brought up and people be made aware to hopefully save somebody else from going through it,” he told WCNC Charlotte. “If we’d have just knew or had an idea, we’d have known what to look for, what to watch for. I’m thankful that River made it out. I got to be thankful for what I do have and if I can prevent somebody else from losing a member of their family, because they don’t know the dangers of it, I feel obligated to do so.”

Contact Nate Morabito at nmorabito@wcnc.com and follow him on Facebook, X and Instagram.